Extending folds for trees (F#)

23 Jul 2017Most articles providing an introduction to catamorphisms I’ve read present concepts of a cata function and a foldl (“left” fold) function and explain how they differ using a binary tree example.

One the most important differences is the input to the function at each recursive step. While cata will receive results of reducing all current subtrees, foldl will only see a single value accumulated across nodes traversed so far.

What we’ll see today is a function that in some way combines those two, so that, at each step, it can use reduced subtrees (accumulated from leaves) and a value accumulated from the root.

If You don’t know the concept of catamorphisms I encourage You to read short or long article (or both) All the code samples from this text can be found here.

Now we can start our little research. Let’s see an example tree type we’ll be working with:

type Tree<'a> =

| Leaf

| Node of 'a * Tree<'a> * Tree<'a>

The Cata function

Let’s discuss “standard”, simple, non tail-recursive cata function.

(*

* type: Tree<'a> -> 'b -> ('a -> 'b -> 'b -> 'b) -> 'b

*)

let rec cata tree leafVal fNode =

let recur t = cata t leafVal fNode

match tree with

| Leaf -> leafVal

| Node(v, left, right) ->

fNode v (recur left) (recur right)

The recursion in this function will first go deep down to the leaves of the tree. There it’ll stop going deeper and just return leafVal. This is where building the final value for the tree starts in the cata function. On the way back to the root, in each node, the fNode function combines results of reducing two subtrees and a value stored in that node.

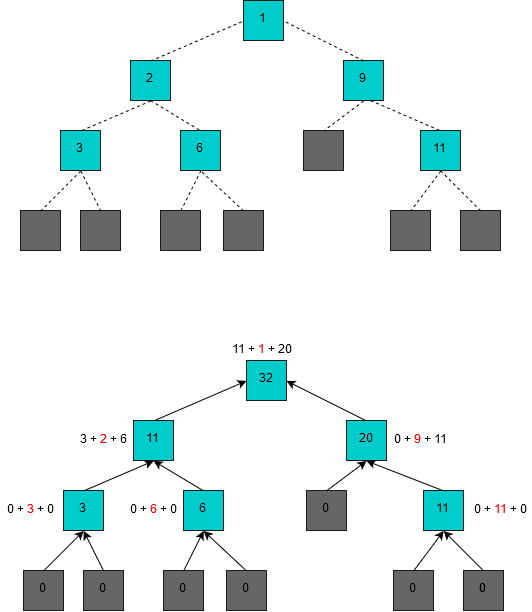

The image below presents this. The leafVal is 0, and the fNode function is just adding values of the current node, left subtree and right subtree. Current node’s original value is marked red. The first diagram on this picture presents the input tree.

While the fNode function was chosen as a simple example, in an advanced usage You could use in Your logic the fact, that You always see three separate values as an input to the function.

The Fold function

Time for a left fold:

(*

* type: Tree<'a> -> 'b -> ('b -> 'a -> 'b) -> 'b

*)

let rec fold tree acc fNode =

let recur tree acc = fold tree acc fNode

match tree with

| Leaf -> acc

| Node (v, left, right) ->

let leftAcc = recur left acc

let newAcc = fNode leftAcc v

recur right newAcc

Once again, we look for the simplicity. We could have a fold version that uses some nice functional ways to achieve tail recursion, but it’s not the goal in this article. What we need to focus on is the fact that our fNode function only uses the single acc argument and passes it to the recursive call.

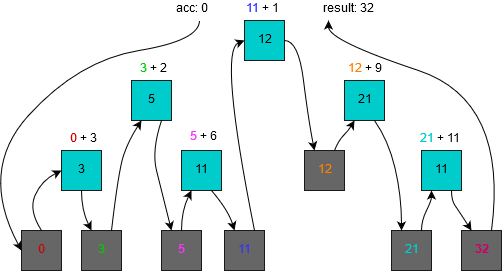

It’ll start with an initial accumulator value and pass it deeper to calculate the left subtree. Once it obtains the reduced value for left subtree (leftAcc) it’ll use it as the input to the fNode function to calculate a new accumulator (newAcc). The latter will be then passed as an input to calculate the right subtree. As before, we can see this depicted on the image below:

Note: the fold function presented here traverses the tree with an in-order method. I couldn’t find any proof but it seems intuitive that, unlike cata, the fold function has the traversing order fixed in a specific implementation.

The use case for mixing both functions

The idea comes from a programming exercise found on HackerRank where the task was to swap subtrees in certain nodes based on the depth of current node.

This involves building a new tree from an old tree - so we need a cata-like recursion pattern. But we also need to know the depth of the current node - which implies we could use an accumulator starting from the root and being increased as we go deeper, somewhat similarly (but not exactly the same way) to what fold does.

Thinking about that further, we may think about the depth as some kind of cumulative cost value. So maybe we could also use our cataPlus function (which we’ll see in just a moment) in problems where at each node a decision how to use reduced subtrees’ values depending on that cost has to be taken.

Let’s first see one possible cataPlus implementation, and then we’ll try to come up with some example of how to use it.

The cataPlus function

(* type:

* Tree<'a>

* -> 'b * 'c

* -> ('b -> 'a -> 'b) * ('a -> 'c -> 'c -> 'b -> 'c)

* -> 'c

*)

let rec cataPlus tree (rootAcc, leafAcc) (fNodeDown, fNodeUp) =

match tree with

| Leaf -> leafAcc

| Node(v, left, right) ->

let recur t =

cataPlus

t

(fNodeDown rootAcc v, leafAcc)

(fNodeDown, fNodeUp)

fNodeUp v (recur left) (recur right) rootAcc

The fNodeDown function updates the “fold-like” accumulator - rootAcc with current value. So this is the function where we would update our cost for next recursive step down towards the leaves. The fNodeUp is the function that can use all three accumulators and current node value. To remind, the tree accumulators are two already reduced subtrees and our current cumulative cost.

A bit more advanced example

Instead of showing diagrams (which in this case would be barely readable), let’s just look at the example promised earlier.

Let’s say we want to have a memorable travel in Europe. There are several cities we always wanted to visit. We’re traveling by car, starting in Warsaw (the capital city of Poland) and we check what are our options for the first city to visit. Then, we check where potentially could go from there, and so on, and so on.

What we come up is a decision tree where each node stands as a next possible destination from previous point (the parent node). We also know how much fuel we’d have to buy in order to reach next point.

[<Measure>]type tanks;

type TravelSegment =

{

Fuel: int<tanks>;

Destination: string;

}

let travelDecisions =

Node({Fuel= 0<tanks>; Destination= "Warsaw"},

Node({Fuel= 5<tanks>; Destination= "Paris"},

Node({Fuel= 3<tanks>; Destination= "Barcelona"}, Leaf, Leaf),

Node({Fuel= 2<tanks>; Destination= "Zurich"} ,Leaf,Leaf)),

Node({Fuel= 2<tanks>; Destination= "Budapest"},

Node({Fuel= 4<tanks>; Destination= "Athens"}, Leaf, Leaf),

Node({Fuel= 1<tanks>;Destination= "Vienna"}, Leaf, Leaf)))

Note: I wanted to come up with a close to real life example that would be simple and useful in demonstrating the concept described in this article. It completely ignores the fact that You could potentially reach a destination in a few different ways (which would introduce some cycles in the graph). It also assumes You can not go back to a previous destination to select a different route.

Our goal is to visit as many cities as possible, but we’re very limited on the amount of fuel we can afford.

Code below presents how we could decide on the best route with cataPlus function.

let inline updateFuelLevel fuelLeft segment=

fuelLeft - segment.Fuel

let decideLongerSubRoute segment lLongest rLongest fuelLeft =

let longerSubRoute =

if(List.length lLongest > List.length rLongest)

then lLongest

else rLongest

if fuelLeft <= 0<tanks>

then []

else segment::longerSubRoute

let mostStopsTravelPlan =

cataPlus

travelDecisions

(6<tanks>, [])

(updateFuelLevel, decideLongerSubRoute)

Here, our journey starts with 6 tanks of fuel as the initial value. At each node, we update the level of fuel by subtracting how much we burnt to reach the current destination. The updateFuelLevel function is responsible for that. It is, in fact, our fNodeDown function, and the initial fuel level is our rootAcc.

The true decision logic happens in the decideLongerSubRoute (which is passed to cataPlus as fNodeUp). First, it’ll check whether we already reached the fuel limit. If so, it’ll return the empty list of travel segments. It means that we simply can’t go any further in this subtree.

If this isn’t the case, it’ll compare current subtrees to find which one offers the longer list of travel segments. Then it’ll simply prepend current node to the longer path and return it as the new path.

Note: even if we may not use results of subtrees because of initial fuel level checking, those values already have been calculated. This is some inefficiency that needs to be considered. It would probably not be such a big problem in a language with lazy evaluation, e.g. Haskell. We could also use the “fold with early exit” technique, but that would add even more complexity.

After running the code, the value of mostStopsTravelPlan is the following list of travel segments:

[

{Fuel= 0<tanks>; Destination= "Warsaw"},

{Fuel= 2<tanks>; Destination= "Budapest"},

{Fuel= 1<tanks>;Destination= "Vienna"}

]

You can verify manually, that three cities are the best we can get. We could potentially visit other three cities (e.g. Athens instead of Vienna), but here the intricacies of our decideLongerSubRoute function come to play.

Afterword

The cataPlus function demonstrates how we can combine value accumulation approaches from the “standard” fold and cata functions. While most of the times we could get off with one of the two latter ones, there are computational problems where they’re simply not enough.

We’ve seen an example of a decision-making algorithm that uses cataPlus and it would be very hard to implement it (if even possible) with simpler functions.

One drawback I see is that with such a big level of abstraction code readability suffers a lot. My observation is, for those who try to switch from procedural to functional paradigm, it takes quite some time to fully grasp the concept of folds.

Personally, I prefer seeing code using functions like sum than doing e.g. fold 0 (+) instead. With more complex cataPlus the readability issues are amplified. It should be almost always used only to define more specialized functions that are then used across all the code.

The implementations presented in this code do not use tail recursion. There are known ways to implement folding functions in a tail recursive ways. It may be a good exercise to try to apply these approaches to cataPlus.

If this post resonates with You in any way, please leave a comment. I’d love to have some feedback.